The State of Wild North Atlantic Salmon

The State of North Atlantic Salmon Report

The State of North Atlantic Salmon Report was published by NASCO in 2019. It highlights the unique life cycle of the salmon, provides information on salmon abundance, the pressures it faces, and gives examples of how these pressures are being addressed. The report shows that wild Atlantic salmon provides society with a host of values, benefits and ecosystem services.

A Species in Crisis

These are challenging times for wild Atlantic salmon. Abundance remains low, or even critically low in some areas.

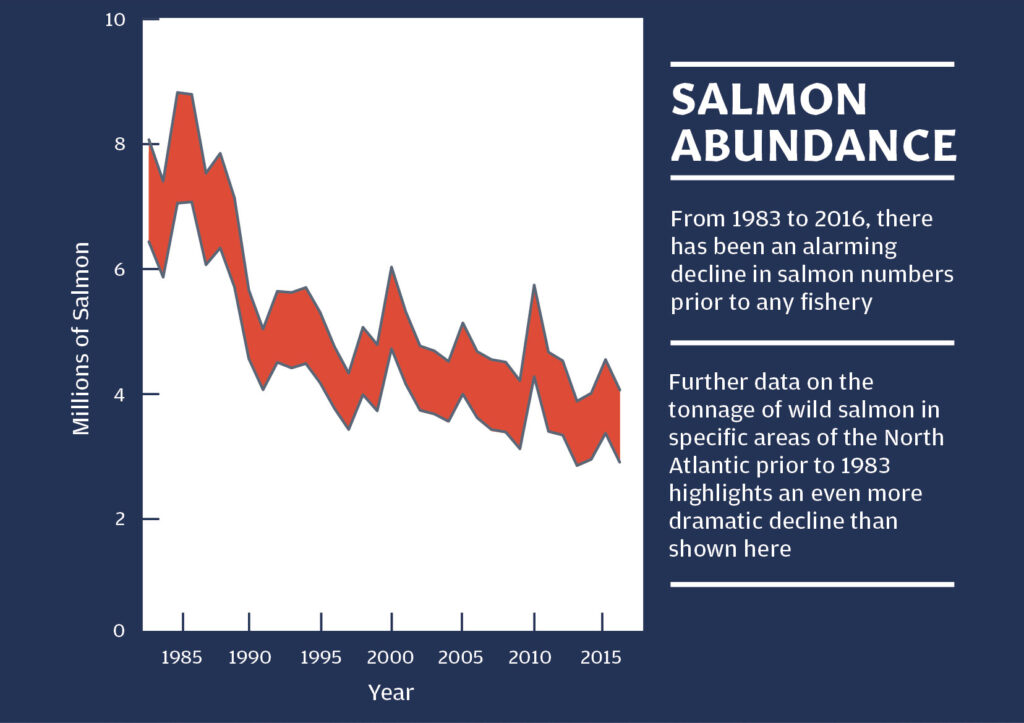

Between 1983 and 2016 – a period of just 33 years – numbers of wild Atlantic salmon prior to any fishing taking place (known as the pre-fishery abundance, or PFA) fell by more than half. The rate of decline was most dramatic from 1983 to 1990, when salmon numbers fell from around seven million to five million fish. And while the rate of decline since 1990 has slowed, a further 33% of salmon have been lost – meaning the number in 2016 was estimated to be around 3.38 million.

During the same period (1983 to 2016), there was a marked reduction in exploitation. Prior to the 1960s, countries made their own rules about salmon harvest with no international discussions. In October 1983, the Convention for the Conservation of Salmon in the North Atlantic Ocean – the birth of the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organization (NASCO) – created a large protected zone free of targeted fisheries for Atlantic salmon in most areas beyond 12 nautical miles from the coasts. This resulted in an immediate reduction in the commercial salmon fishery which, at its peak in 1973, harvested some 3.5 million salmon.

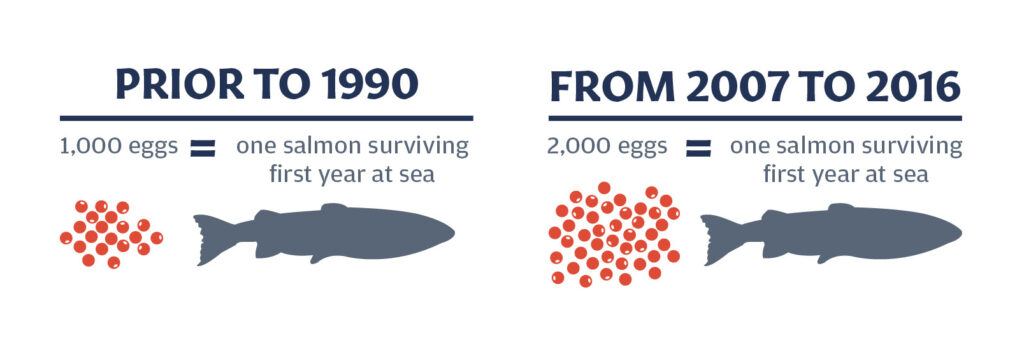

Despite these significant fishery reductions, numbers of Atlantic salmon continue to decline. We know this in part through the tagging of several million fish each year for assessment and research purposes. It now (since 2007) takes about double the amount of eggs to produce one adult (compared to the period prior to 1990) that will return to that same river to spawn – an indication of the multiple pressures facing the species throughout its complex life cycle.

A Special Life Cycle

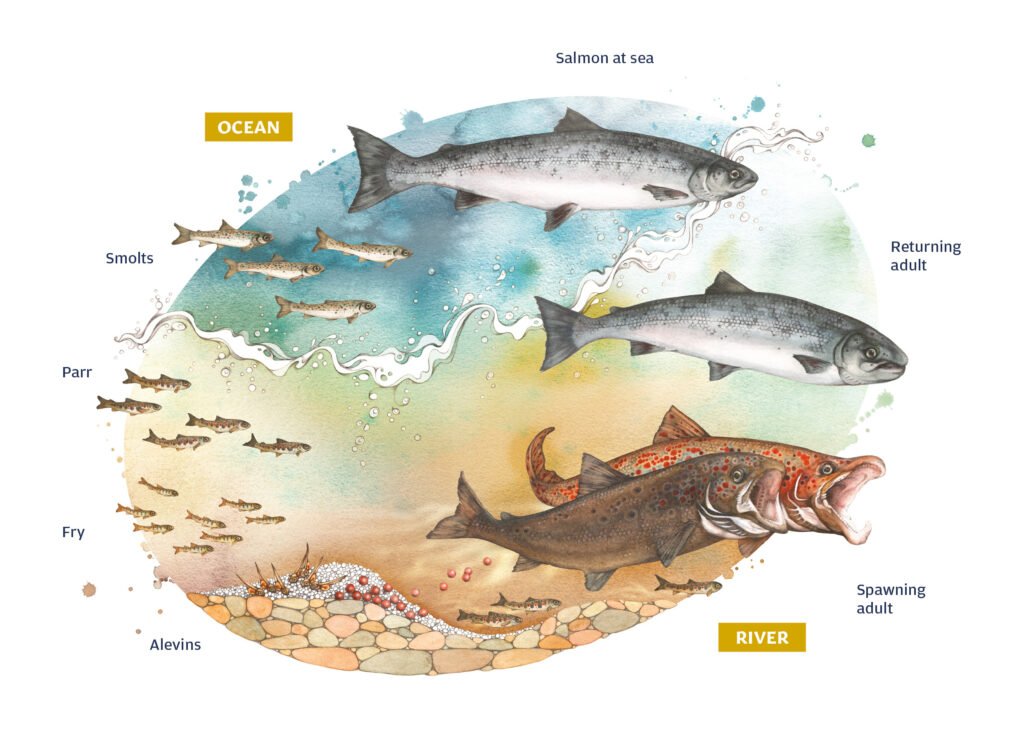

The North Atlantic salmon begins life in the rivers of countries that surround the Atlantic basin – from Portugal, Spain and New England (USA) in the south of its range to sub-Arctic Canada and Russia in the north. Spawning occurs in the autumn and winter, with female salmon depositing between 1,000 and 2,000 eggs (ova) per kilogram of body weight into a nest (or redd) made on the gravel bottom of rivers.

Hatching occurs the following spring. The young salmon (or alevins) are nourished by the yolk sac until they emerge from the gravel as fry to commence feeding. After the first year of life, the young fish are known as parr.

Following a period in fresh water, which can range from one to seven years, the parr undergo an enormous physiological, morphological and behavioural change, known as smoltification, that allows them to adapt to the salt water of the Atlantic Ocean. These smolts, as they are now known, migrate to the ocean in the spring and, after one or more years at sea, return as adult salmon to their rivers of origin to spawn. Once back in fresh water, they change colour to a mottled reddish-brown. The male fish also change shape, developing a prominent hook or kype on the lower jaw. Most salmon die after spawning, but a small proportion, mainly females, will spawn again following another trip to sea.